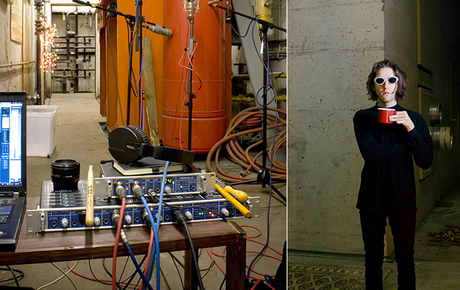

How to catch a ghost? German musician and sonic experimenter Philip Albus discusses making field recordings and impulse responses with the RME Fireface UC and Fireface 800 audio interfaces.

The RME Fireface UC is a professional-level audio interface, delivering 36-Channels of pristine audio via USB 2 for both Mac and PC based systems.

The characteristic transparent sound of RME audio interfaces is well-documented – what you put in, you get out – providing the user with an unmatched versatility when it comes to recording. Along with forming the centre of project and professional studios around the world, RME’s products can also regularly be found in use by broadcast, academia and the scientific community.

This versatility also makes an RME interface the perfect choice for location sound recording. In this article, Philip Albus gives us an insight into his methods when making field recordings. He also discusses taking impulse response readings, which allows him to capture and recreate the natural sound of the spaces he records in with a convolution reverb…

“A song sleeps in all things,

Which dream on and on,

And the world begins to sing,

If only you find the magic word.”

As Joseph von Eichendorff states in his famous poem “Wünschelrute” (“Dowsing Rod”) from 1835, some of the most fascinating songs in this world aren't really obvious. Like ghosts they are occluded and well hidden from our everyday perception. And sometimes the “magic word” to uncover them can be a simple sine sweep.

Already back in my school days I was fascinated by the sonic content of the world and its non musical objects around me. I would organize field recording excursions for my schoolmates to hunt down curious and unexpected sounds employing battery driven tape recorders and dictaphones. Most of those tapes I still have.

However I learned that there is something more subtle and mysterious than the random sound of found objects. It was about two years ago that when by chance I got access to an abandoned industrial facility near the German city of Gießen. Being socialized by the music of groups like Einstürzende Neubauten, Throbbing Gristle or Nine Inch Nails this felt like a post-punk teenage dream to come true. So it didn't take very long until I became completely absorbed by the place where I soon would spend almost every free minute. One of its most striking aspects besides the early 50s German industrial charm was its sound.

Spanning over 2000m² it comprised all sorts of amazing or simply weird sounding acoustical environments – even including a high pressure room one had to enter through a massive (and not less amazing sounding) iron door. I was in love. And I realized that what was special about the factory wasn't so much about the things I could record in it but more about what the factory did to those things. Yet since I also knew that my relationship with this place was a rather finite one, I needed to find a way to preserve its acoustical heritage before the bulldozers came to rip it apart. That's when I started to hunt for ghosts.

Spanning over 2000m² it comprised all sorts of amazing or simply weird sounding acoustical environments – even including a high pressure room one had to enter through a massive (and not less amazing sounding) iron door. I was in love. And I realized that what was special about the factory wasn't so much about the things I could record in it but more about what the factory did to those things. Yet since I also knew that my relationship with this place was a rather finite one, I needed to find a way to preserve its acoustical heritage before the bulldozers came to rip it apart. That's when I started to hunt for ghosts.

The principle of extracting the acoustical properties of a place is fairly simple: A space approximately acts like a so called linear time-invariant system (LTI system). That means a room will react to a signal with a low amplitude in just the same way as it reacts to a signal with a higher one. And it will do that in an unchanged manner no matter if it is full moon, half moon or not even night-time at all. Because it is time-invariant. Such a LTI system can be described completely by how it reacts to one single sample of audio, which is equal to one infinitely short but very loud impulse (those are also called “dirac-impulses”).

When you deliver such an impulse into the space you get that space's “impulse response”. And this is actually all that is needed for recreating the effect a room has on any given audio. However by attempting to play an infinitely short but very loud impulse through a speaker you might easily end up with not having a speaker anymore. So a much more preferable method is to use exponential sine sweeps which are played into the room and recorded by a set of microphones. By employing a process called “deconvolution” we can transform the recorded sine sweeps into the impulse responses we are looking for. These can then be loaded up into any convolution engine to apply the sound of the room to a given audio file. (A great free one is the “SIR1” VST-plugin from “SIR Audio Tools” by the way. http://www.siraudiotools.com/)

However all of the above put into practice will inevitably render you a little crazy. For me it usually means spending my nights at remote places I gained access to by tedious negotiations while fighting with the whims of nature and civilization. A high quality RIR measurement requires silence. A busy street next door, a tram line, wind, rain or even animals like birds or some hyperactive rodents can make your job a mission impossible – and that often right after you just set up all your gear, managed to power it up, eliminated hum loops etc. and found the magic spot for placing mics and speakers.

However all of the above put into practice will inevitably render you a little crazy. For me it usually means spending my nights at remote places I gained access to by tedious negotiations while fighting with the whims of nature and civilization. A high quality RIR measurement requires silence. A busy street next door, a tram line, wind, rain or even animals like birds or some hyperactive rodents can make your job a mission impossible – and that often right after you just set up all your gear, managed to power it up, eliminated hum loops etc. and found the magic spot for placing mics and speakers.

The places I'm after aren't musical per se and in winter times you better bring a water cooker and a warming blanket (in case you have electricity). My inherent obsessiveness has to make up for my lack of patience here. And there are the moments I wish that I'm not just confusing “passion” with some kind of clinically relevant madness. Nevertheless I personally believe that in many cases both are somewhat linked.

"Due to their very neutral and transparent preamps they lend themselves perfectly to the purpose of documenting spaces.

Plus: They look damn good next to an industrial switchboard."

So in a complex and challenging work environment (especially when paranormal activities are involved) the least thing I want to deal with is unreliable and moody equipment. Of all the audio interfaces I have worked with in the past the RMEs are the ones that never let me down on a single occasion. Their performance is stable and they are robust like little tanks that proofed to defy icy temperatures and factory dust much better than me. I currently use a Fireface 800 (the Fireface 800 has been discontinued – please see the RME Fireface 802 instead) as well as a Fireface UC. Due to their very neutral and transparent preamps they lend themselves perfectly to the purpose of documenting spaces. Plus: They look damn good next to an industrial switchboard.

Philip Albus is currently building the “Klangarchiv Gießen” RIR-database that collects lost places all over Germany and will go online in late summer 2016. When he's not hunting ghosts or busy studying neuropsychology, he's involved in making records, performances or gigging around Europe with various projects and bands.